Is China a market? A partner? A competitor? Yes. Yes. And yes.

Submitted by Jim Mahoney on

Daily media reports on China are laden with coverage on both 1) massive resource-intensive industries and their devastating pollution footprints causing health scares, environmental protests, and economic constraints, and 2) debate on whether China will (or will not) be able to rejig the economic model onto a more sustainable footing amid escalating urbanization, demographic and social pressures. Whether you are bullish on China’s economic and environmental future, bearish, or just confused, you will have no shortage of data, headlines, and “expert” tweets to cite in arguing your views.

The information onslaught is luring ever more cleantech companies from around the globe to China seeking business in what is a staggering and decades long clean-up and economic advancement effort.

At Kachan, we are addressing many more China ‘macro’ questions as international firms increasingly weigh cleantech opportunities against growing economic uncertainty: Is China’s economy already bigger than America’s? Will China keep humming along or stumble under debilitating housing or debt crises? Is China winning or losing the clean energy race?

China’s medium and long-term outlook has its place in corporate planning. The crucial take-away for cleantech firms though is more straightforward—regardless of how sharply China’s economy continues to slow and ebb, the world’s 2nd largest economy continues growing in absolute terms and the requirements to feed that growth more productively (both in economic and environmental terms) will only intensify for many years.

Two corollary messages are also key. China is actively seeking useful western cleantech knowhow; so yes, great opportunity abounds. Secondly, central policy clearly strives to develop Chinese companies and industries as leaders in clean and green technologies and services—both for deployment, jobs and higher-value industry at home, and also to be able to compete globally. Successfully selling and collaborating in China comes hand-in-hand with effectively maintaining control of the core value you are bringing to China.

China Leading in ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’

China continues investing more into clean energy manufacturing and deployment than any other country; in 2013, China’s investment into clean energy deployment outstripped all of Europe’s. National government bodies regularly announce world-leading sustainability targets plus an extensive array of policies and spending to help achieve them. At the same time, China maintains annual global leadership in coal consumption, cement and steel production and the consequential pollution and waste trails damaging air, water and soil.

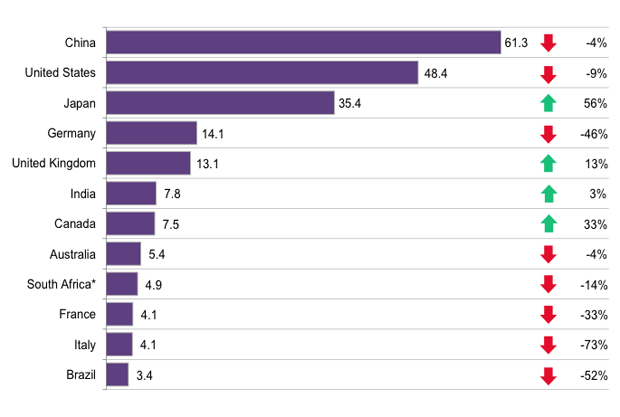

Top countries with new investment in clean energy (2013). Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance. (Note: Total values include estimates for undisclosed deals. *Corporate & government R&D is not available for South Africa, but is included in the other countries.)

So, should China be lauded for impressive targets to reduce the fossil fuel component in the energy mix, or be accountable as a top ‘dirty’ resources guzzler and polluter? Is China a leader in sustainability by driving solar and wind costs down and benefitting all, or is its cleaner energy juggernaut simply a zero-sum mercantilist dagger forged from unfair state subsidy designed for domestic job creation, intellectual property transfer, and below-cost product dumping? Canadian Cleantech firms looking abroad can investigate both sides of these debates for capturing opportunities in China—identifying problems they can solve and/or capitalizing on investment incentives and commercialization advantages through collaborative tie-ups.

‘Brand Canada’ is a good start

Canada is focused on growing exports partly by ‘touting its own horn’ more effectively. Canadian cleantech is gaining recognition for punching above its weight in research and innovation investment into technologies with global applications, and for creating jobs in high-value segments. Marc McArthur, who heads Ottawa-based cleantech advisory Crosstaff Solutions, believes that effectively promoting these trends empowers cleantech providers with a compelling sales message to take abroad. McArthur stresses that “not surprisingly Canadian sustainable technology strengths relate very much to Canadian strengths overall—bioenergy, biomaterials and other bio-sectors, as biomass and our boreal forest link one end of Canada to the other in one continuous narrative of industry, history and expertise, as well as water, and oil & gas—again for reasons that are obvious when you look at Canada's make-up as a country.”

Canada‘s main limiting factors for cleantech deployment are a relatively small size as a marketplace and inadequate access to growth funding. McArthur advocates building capacity within Canada’s SME's to step up to the challenge of addressing global markets because “the problems that sustainable technology companies solve are felt the most in other parts of the world that are not blessed with as many resources per capita.”

China’s impressive sustainability goals, host of markets, and growing resolve for cleaner and more efficient growth make the country well worth a look, be it to grow exports, license technology, or find investors or manufacturing and channel partners. If you have something special that impressively solves efficiency and waste problems, Chinese parties will want to learn about you. To get noticed above the crowd—the growing line-up of organizations (both foreign and domestic) that are also knocking on the same doors in China—Canadians will benefit by delivering a more impressive ‘Canadian knowhow’ message and also by understanding and effectively navigating the interplay of markets-partnerships-competitors.

China markets are many, but not for everyone

The world’s largest user of energy and of major commodities from coal to copper and rice to soybeans, the largest producer of cement, steel, rare earth elements, pork, and history’s largest urbanization build-out is guzzling energy and water, and polluting too much. China has heaps of market opportunities right across the cleantech spectrum, including energy, air, resource use, water, industrial efficiencies, more livable cities, waste, and safer food.

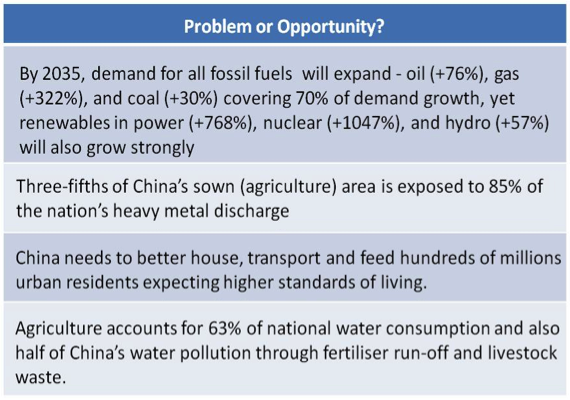

Consumption and emissions challenges in China. Source: BP Energy Outlook 2035; China Water Risk, McKinsey Global Institute

Consumption and emissions challenges in China. Source: BP Energy Outlook 2035; China Water Risk, McKinsey Global Institute

China is increasingly addressing these challenges with more detailed rules, impressive spending goals and incentives to apply and develop technologies that allow cities to produce and consume more responsibly. Opportunities for Canadian cleantech are in top-notch technologies and services that directly help these local markets achieve their goals.

As inviting, mysterious and excitingly “huge” as China’s potential is, executives are cautioned to make sure that their smart business sense—the thinking that has led them to their current level of success—does not get left at the border when entering the country. Broad strategic questions need to be supplemented with objective consideration of basic market-entry factors to consider: Is foreign participation restricted in your target sector? Do local market licensing hurdles for your product favor domestic companies? What is your IP risk appetite? Are you flexible in equity structures or payment terms criteria? Do potential local partners have competing interests? Will you be able to cost-effectively deliver after-sales support?

If your answers to these early questions point to pursuing China, great! Gather more information, get your visa, book your flights, and start prioritizing and acting on your options. One strategic option to keep in mind (and one that is not considered often enough by many western cleantech executives) is ‘not’ pursuing China. For certain clients, Kachan has recommended objectively comparing the risks and costs of China with similar opportunities in other emerging markets which have similar goals for energy security, healthier citizens and more competitive industries. While taxing even more valuable management time and attention up front, an evenhanded analysis pointing to a “no go” on China (at least for now) helps companies allocate resources more effectively on markets or projects judged to have quicker approvals, clearer procedures, or less risk.

Too often, western firms that end-up walking (or running) away from China shell-shocked, frustrated or just plain exhausted, report in hindsight that they did not allot enough focus to early strategic questions. They also frequently did not engage in, or manage well enough, necessary partner relationships to gather and assess accurate information for market entry and expansion decisions.

China partnerships are essential

In the U.S. and Europe, government involvement in cleantech often gets put through the wringer with grumbling over where and how funding is allocated or frustrations over unpredictable pendulum swings in policy signals. Kachan & Co. has been vocal in advocating smarter government support for cleantech—reducing financial support to specific “chosen” technologies while focusing more efforts to define achievable standards, codes and green targets—and then standing back while industry and private enterprise do their job in deciding the technologies and solutions that work.

For cleantech vendors and investors in China, ‘government’ isn’t a bad word, it is an essential partner. Major sectors urgently needing and attracting cleantech are largely state-owned, with western and private participation subject to central government direction. According to Shanghai-based Patrik Lund, Asia head for Energy and Industry with global environmental engineering group MWH, the challenge, and driver of much complaining from the cleantech world in China (both western and Chinese), is at the local level and the ambiguity and inconsistencies in the myriad ways provincial and local governments interpret policy or in questionable transparency in how they implement their administrative and approval procedures which decide access to opportunities.

As an example, regulations and procedures set by Chengdu to meet or exceed a emission reduction target for example might dictate a far different strategy than a similar project in Hangzhou that is pursuing the same target. As Lund explains, “cities can be at different stages of development, rely on different industrial bases, or have different constraints—say water in the north versus lack of usable land in another region. Therefore they will have different priorities and, quite reasonably, differing perspectives in how they can meet a national target.”

Relationships with relevant local officials and well connected state-owned or private companies and economic development zones have to be evaluated and developed for western firms to make progress. Even in sectors and segments where foreign-direct investment is encouraged, ostensibly giving western firms complete legal and administrative access to markets, local partnerships are still necessary. Direct access does not remove any of the tedious work required to move forward, for example useful information, necessary approvals, sales and supply channels, support services. These channels are fragmented, can rely on rock-solid personal connections, and may be subject to administrative barriers favoring local competitors.

For cash-strapped and under-resourced SMEs with limited bandwidth to accomplish these tasks alone, essential partnerships very often also include knowledgeable and reputable intermediaries (whether Chinese or western-invested) on the ground that are plugged into the relevant local sector channels and decision makers.

China competitors have the home-court advantage

Western cleantech companies will generally face three classes of potential competitors in China: Other western firms developing and selling similar (high-tech, high performance, high priced) products and processes; Chinese incumbents or companies quickly bringing substitutes to markets (usually lower price, less performance); and customers and partners (Chinese and/or foreign-invested) who develop into competitors.

Canadians have quality innovation and high performance solutions to offer. The ‘hardware’ portion—generic components, supply logistics, or manufacturing infrastructure for example—can be localized very well to drive out costs and certain higher functionality that the market won’t pay for. Your Chinese vendors and partners can do this well and will compete (either with you, or amongst themselves) for this part of the business.

The Canadian firm’s valuable competitive advantage will be in the ‘software’ contribution such as essential IP and regular upgrades, highly specialized management skills, or unique support service expertise. This proprietary value is what China mainly wants (and in many cases why China is receptive to working with you). If your customers and partners become able to deliver the ‘software’ without your input, they may soon be competitors.

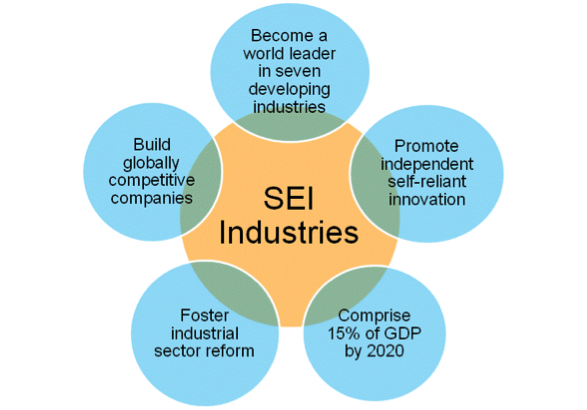

Central policy is clear on attracting advanced western technology that benefits China. Very often, and especially in industries that are slowly opening up to direct foreign investment and participation, market access is tied to trade-offs of technology or knowhow transfer to some degree. A relevant example involves the Strategic Emerging Industries (SEIs) program.

China's Strategic Emerging Industries (SEIs)

| Energy Saving and Environmental Protection |

| New Energy |

| Biotechnology |

| Advanced Equipment Manufacturing |

| New-Energy Vehicles |

| New Materials |

| Next Generation Information Technology |

The seven SEIs are advanced, knowledge and tech-centered industries (each of which have relevance to cleantech) with state-level support for preferential tax, fiscal, and procurement policies. The aim is promoting investment into higher-value technologies that improve industrial efficiency, clean-up the environment, create jobs, and most importantly, develop advanced knowhow for Chinese firms to be able to compete, and lead, in these relatively new industries still with no (or few) global leaders in place yet. Chinese partners will be thinking long-term of how they can achieve these SIEs goals with your technology and knowhow, and not necessarily with you.

China's SEI policy goals. Source: U.S.-China Business Council, 2012

The issue for westerners is to carefully balance their own business priorities (protecting core IP and accessing markets) with Chinese partner goals. MWH’s Lund, who has worked with multinational and Chinese energy and resource giants for over 15 years, recommends two approaches: “Always aim to upgrade your own IP, be it technology or services, and align Chinese partners with clear incentives to protect your IP as the most direct way to reach their goals.” If not, your partners will quickly begin finding ways to replace you or compete with you, “which is not something unique for China, but what you would expect in any competitive business environment”, according to Lund.

Having the patience, management capacity, strategic flexibility, and the budget to understand and carefully manage the simultaneous rewards and risks in the constantly interacting markets-partners-competitors playing field may well be a prerequisite for success.

This is the second article (the first article is here) in a multi-part series by Kachan & Co. in which we identify a range of opportunities, discuss common risks, and suggest a few tips that Canadian cleantech companies interested in China might well consider. We hope you find these insights useful.

Jim Mahoney is Managing Director of China at Kachan & Co. and a former Managing Director-China for Cleantech Group. He has lived and worked in China for 18 years advising and managing western SME investments and operations in China. He can be reached at jim@kachan.com.