China questions Canadian cleantech companies should consider

Submitted by Jim Mahoney on

Canada boasts 700 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) developing innovative cleantech and sustainable development technologies, more than half which already export, and up to 10,000 SMEs involved in solutions and sectors where cleantech is applicable. Common challenges for many of the younger or earlier stage firms is accessing the development capital and industrial partners for requisite trials and pilots needed to get their innovations proven at industrial scale and into viable markets.

China has hundreds of bustling, congested cities urgently needing to clean-up dangerous pollution footprints while striving to shift to cleaner, more efficient, and higher value economies that meet and achieve increasingly aggressive clean-up targets set down by the central authorities. Local Chinese governments and companies are actively seeking, both at home and abroad, practical and affordable solutions and expertise which they can use now, or can finish developing in short order and then quickly rollout. For effective technologies and solutions that directly solve specific problems, Chinese cities are prepared to bring attractive monetary and regulatory incentives to the table.

China is “cleaning-up” because it has no choice

The overriding global drivers of cleantech—growing demand for finite energy, water and natural resources to provide for growing populations seeking higher standards of living—are only becoming more pronounced. Nowhere is the necessity to do more with less as evident as in China. Daily media headlines portray China as the “poster child” in the dilemma of providing more power, cleaner water and safer food to massive urban and rural populations, while reducing regular episodes of “off the charts” air, treating vast swaths of unsafe water, and rehabilitating sick land scattered throughout the country.

Downtown Beijing on a relatively good air day, and a bad air day. Source: Kachan & Co.

In advanced economies—with high standards of living and industrial chains that are generally more efficient and less ‘dirty’ than in emerging countries—pursuing cleaner energy sources, less toxic industrial inputs, or fewer harmful emissions can sometimes be looked at as “nice-to-haves” rather than “need to haves.” For China, though, cleaner water, air and safer food are all necessities now.

The country’s leaders are determined to re-vamp the heavy energy and resource intensive industrial structure. They recognize that if they do not aggressively build on impressive initial efforts for greening ‘dirty’ industries and creating cleaner, higher value industries now, they will face exponentially higher costs down the road in economic constraints and higher social costs of vast numbers of angry, unemployed, and chronically ill people. These challenges are steadily amplified by the country’s efforts to secure energy, mineral and food resources across the globe that will house, transport, feed and entertain an urban footprint that is expected to grow from between 100 million by 2025 and 350 million over the next 15 to 25 years.

Indeed, China’s fossil fuel consumption (70% of energy demand growth up to 2035), harmful emissions and water strains resulting from the urbanization drive will continue to rise for many years. The good news is that China is vigorously adjusting regulatory direction and allocating money and incentives aimed at increasing the proportion of cleaner inputs and more efficient usage of energy, water and resources.

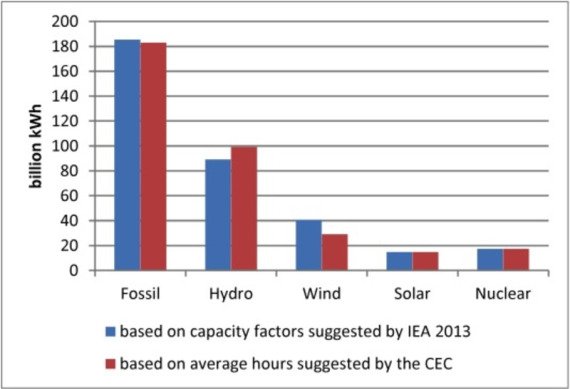

New Energy Generation (taking into account renewable generation capacity factor) for Electric Power in China in 2013. Source: Matthews and Hao, 2014

Cleantech’s ‘second wind’ is ripe for leveraging China opportunity

The cleantech sector has faced gusty headwinds in North America and Europe over the last few years. Anticipated game-changing breakthroughs did not materialize. Technology roadmaps and commercialization proved far longer and more costly than envisioned (in part due to weak financing support in the wake of the global recession). The resulting poor returns not only helped sour investor and business confidence in the sector’s promise of a cleaner tomorrow, but also helped amplify public debate on the merits of regulation and tax-payer money supporting more costly cleantech development at the expense of shorter-term economic levers such as cheaper traditional fuels, jobs and social programs.

As Kachan & Co. has recently published, cleantech is seeing a comeback on more market-driven terms and signs of renewed investor interest. “Pick and shovel” products (e.g. efficient lighting, low cost renewable energy generation, power data and management software) are quietly becoming entrenched across the globe. Cities and large industrial players are increasingly partnering with cleantech firms to expedite their own innovation goals and at the same time helping SMEs bridge financing gaps, gain domain knowledge, speed industrial pilot projects, and leverage scales of production and established distribution channels into markets.

Like their counterparts across the globe, quality Canadian cleantech start-ups and SMEs that have survived the tough years did so by learning to deliver more practical benefits to specific sets of customers, embracing less capital intensive business and financing models, and adopting more professional management and marketing principles.

Matching Canadian Cleantech Innovation with China’s strengths

More and more of these successful, or at least surviving, cleantech firms are investigating China to leverage any number of inviting incentives from local authorities, companies and industrial zones—investment capital, low-cost financing, regulatory and tax support, and extensive industrial infrastructure and supply chains—that help speed technology development, testing and production.

Marc MacArthur, CEO of Crosstaff, an Ottawa-based sustainable technology advisory and project development firm, judges Canada is doing an excellent job encouraging cleantech innovation through research and early-stage technology development. According to MacArthur, “Canada currently leads the G7 in post-secondary research investment. Programs like the Scientific Research and Experimental Development tax credit (SRED), the $1B Sustainable Development Technology Canada fund (SDTC), Industrial Research Assistance Program (NRC-IRAP), Climate Change and Emissions management Corporation (CCEMC) and the Build in Canada Innovation Program (BCIP) to name a few have been tremendously helpful to sustainable technology companies and are regarded as models to emulate in other markets”.

Where MacArthur sees major hurdles for Canadian firms though is in Canada’s relatively small market size due to its small population, abundance of resources and relatively few overt environmental challenges compared with other markets. He also cites inadequate technology deployment funding including venture capital, and a manufacturing base that is not robust enough to get many of these valuable solutions tested and proven at industrial scale.

Enter China, a potential marketplace not encumbered by those limitations. China by no means will be the answer for everyone. Yet the size of potential markets and an abundance of regulatory and monetary incentives for cleantech solutions, make a persuasive case for Canadian cleantech firms to take a close look.

Western cleantech start-ups and SMEs mainly come to China for one or more of:

- a market for current, proven cleantech and sustainable solutions;

- a source of capital, finance or low-cost R&D and manufacturing resources; or

- a collaboration platform for supplying products and solutions to global markets.

So, how do Canadian cleantech SMEs get noticed, gain access to, and develop such opportunities in China? There is no cookie-cutter approach. For one, cleantech covers a broad umbrella of sectors seeking cleaner inputs, more efficient processes and less waste applicable across almost any sector. Secondly, China is made up of dozens of regional and localized markets (as opposed to one huge bucket) each with their own priorities, administrative procedures, and institutions tasked with planning and implementing their clean up.

Canadian SMEs interested in China therefore should consider focusing initial efforts on gaining the accurate and relevant information that will help them i) understand whether they indeed have legitimate opportunities to pursue, ii) understand clearly what specific value and proprietary knowhow they are prepared to bring to the opportunities, and iii) understand the particular partnerships they will need to develop and maintain in order to access and develop the opportunities. A useful exercise to help assess potential, risks, and options involves considering three key questions:

- What does China want from Cleantech?

In a word, China wants “everything” – enough energy and resources, cleaner air and water and food, more livable cities and higher-value industry.

China wants cleantech that capably addresses problems targeted in national policy goals. Local governments are increasingly tasked with meeting environmental targets, making their cities more sustainable and building cleaner industries. China policy not only strives to rollout such solutions at home, but also to acquire or co-develop the know-how to own and build up leadership in these technologies to take abroad and compete globally.

China wants demonstrated successful technologies and solutions that are available now (or soon). More often than not, you must have something tangible and proven (either through pilot projects in China, or by bringing the Chinese to working installations abroad). China is a recent arrival to globally competitive industries. The country does not have 50 years of knowhow through R&D and continuous strings of tech development iterations, nor do they have the inclination to develop these capabilities themselves. It is cheaper and faster to buy and license western technologies, and if possible continue developing them.

China wants cost-effective cleantech. China’s world-class supply-chain and manufacturing infrastructure developed largely based on low-costs (e.g. abundant labor, low-margin/high-volume economies of scale, weeding out non-essential functions and logistic costs) and this is a competitive advantage western firms can trip over by fighting it, or benefit from by embracing it. China’s current industrial infrastructure largely remains far more wasteful, energy guzzling, and polluting than in advanced economies like Canada. Therefore, China seldom pursues the latest, highest priced solution. For example, a 3rd-generation process say—that delivers 50% functionality compared to the latest 5th-generation process, but at just 1/2 the price—can still provide acceptable performance benefits at an acceptable margin. As China rolls out that solution at home, and later abroad, lower-cost will be a main competitive differentiator.

Simon Littlewood, CEO of China-based New Climate Group, points out that when a western solution clearly meets the above criteria, “the local project owners will be proactive in a number of ways, such as helping getting relevant approvals, working with both government and private funds to quickly create a comprehensive funding package.” Littlewood, who has been investing in and developing sustainable solutions for markets in Asia and China for nearly 20 years, relates that the most successful projects start with his Chinese partners clearly identifying specific, pressing market need. With that information, his teams then find and work directly with the investors, governments and cleantech executives that are laser focused on the specific solutions and applications the Chinese projects require.

- Is my Intellectual Property (IP) safe?

For small, innovative cleantech companies, IP is often all they have to offer and hence protecting it is job one, and so a workable IP strategy is often a pre-requisite for China entry. Common tactics include a robust patent portfolio in China, “blackboxing” the essential codes or recipes, keeping the latest 15% of knowhow in-house while licensing the rest, breaking up essential knowhow in separate ‘silos’ across various supply chain partners, and utilizing clear rules and procedures for non-disclosure and non-competition in staffing and 3rd-party contracts.

New Climate Group’s Littlewood offers sound advice. He agrees that one’s IP strategy is critical, yet must be flexible, and cautions that “even with a smart strategy in place, in today’s global world, if you’re not constantly developing your IP then you are going to be dead in the water anyway. The best long-term solution is a strong Chinese partner in a well-defined relationship that is properly structured to make it in your partner‘s interest to also protect your IP.” As an example, Littlewood points to products or services that require continuous support or upgrading to remain competitive, “if you as the Canadian partner are not the ones able to, or agreed to, provide that, then you basically have no lasting value for your Chinese partner, and they will look to move on without you.”

Interestingly, western company executives with extensive time and experience operating in China, more often than not, place IP protection rather far down the list of issues and priorities. Much more of their time is occupied handling operational issues such as difficult administrative approvals, non-transparent market information, local protectionism, talent retention, and the speed of market changes and competitor moves. These same executives often stress that many of the most compelling opportunities that collaborating with Chinese firms can offer—squeezing out unnecessary costs, fast scale-up, or exclusive customers—can be lost to companies that maintain less flexible or over-zealous focus on 100% IP protection.

- How do I approach China?

Have something ‘special’ to showcase.

In many cases, Canadian offerings (innovative, niche, high-tech) will be competing with other western countries’ offerings (high tech, high performance, high cost) more so than with Chinese competitors (often lower-tech, less functionality and lower pricing). Cleantech innovation developed within Canada’s traditional forestry , mining, and oil and gas sectors are just a few examples of particular strengths that Canada is developing to deliver cost, quality and environmental performance at home. These are three very important sectors in China that must adopt more sustainable technologies to meet increasingly stringent environmental targets.

Get visibility in front of the right potential partners.

Peter Corne, Managing Partner of Dorsey & Whitney LLP in Shanghai, points out that “the market situation here is very fluid and very much driven by whom you meet and the way you follow up who you meet. Chinese companies can often be run like little fiefdoms so it is essential to reach the decision makers at the top. This is difficult to do, especially for SMEs with limited resources.”

Corne, a 20-year China veteran who leads his firm’s well-respected China cleantech practice, relates that plenty of westerners waste time in early efforts by going through middle management whom they have met through trade shows, business delegations, or responding to correspondence initiated by Chinese firms. These Chinese contacts do not have decision making power and may not have access to that level. Littlewood also recounts that many westerners also spend valuable time in proactive googling, emails and phone calls, which shows initiative and can indeed lead to preliminary meetings, “for start-ups and smaller firms with minimal resources it may be a long while before identifying and reaching genuine potential customers or strategic investors, not to mention the time involved in relationship building.”

Both Corne and Littlewood emphasize the benefits of getting to know and utilizing effective local partners. These mainly being the companies and government officials responsible for the specific types of projects and applications you are looking for. For firms that are new to China, valuable partners might just as importantly be plugged-in advisors and professional service companies and on the ground, who have the domain knowledge and the requisite relationships with the relevant heads of local governments and companies that you need to get to know, collaborate and negotiate with.

Have a presence “on-the-ground”.

To be able to accomplish the first two tasks above, a capable person or a partnership resource is needed in-country. Corne stresses, “ that resource on-the-ground is essential to be able to get a proper feel for how things are working here day-to-day, to identify and leverage opportunities as they arise, and just as importantly, to properly relay that timely information back to HQ to gain or maintain leadership buy-in and decision making feedback.”

“Cleantech firms who do not make that commitment are just too slow for the speed that China moves, and invariably struggle to make much progress,” stresses Corne.

This is the first article in a multi-part series by Kachan & Co. in which we identify a range of opportunities, discuss common risks, and suggest a few tips that Canadian cleantech companies interested in China might well consider. We hope you find these insights useful.

Jim Mahoney is Managing Director of China at Kachan & Co. and a former Managing Director-China for Cleantech Group. He has lived and worked in China for 18 years advising and managing western SME investments and operations in China. He can be reached at jim@kachan.com.